Hey guys! Nuclear Power is a technology that has a dedicated, enthusiastic group of followers. And it really is a pretty interesting technology! I was actually completely obsessed with the Manhattan Project when I was 20.

Nuclear power is, unfortunately, a very expensive source of energy. And even worse, it keeps on being even more expensive than it’s supposed to be. Nuclear construction projects have, again, and again, faced terrible cost overruns and delays. It’s really a shame, because it would be great if we could use such a source of carbon free energy, but again and again, they’re unable to do it on time and on budget. A large number of pundits have claimed that nuclear power’s (relative) failure is caused by NRC overregulation. I have very carefully read many critiques of the NRC, and it is my opinion that I have not seen any essay that persuasively makes the case that Nuclear Power’s unfortunate cost problems are caused by NRC overregulation.

America definitely has some overregulation!

Let’s start with the fact that we definitely have some overregulation now! In particular, I’m strongly aligned with the YIMBY movement and I think that local zoning rules are really the go-to example of a regulation that is really, well, bad.

Another good case of overregulation frequently cited by deregulators is NEPA. The National Environmental Policy Act is an administrative law that nominally exists to say that the government has to carefully study the consequences of building new infrastructure, but it’s almost always invoked in bad faith in a way that effectively makes it a “tax on progress.” In fact, in many cases the people filing NEPA lawsuits more or less explicitly admit that the official justification of carefully studying consequences is bogus, and the real reason is they just don’t accept the verdict of our democratic political system, and they want to make the legal costs of decisions the dislike so high they have to be abandoned. And even in the cases where NEPA is being invoked in good faith, my general sense is that the cost to society of delaying these projects for years and years just far outweighs any meager benefits of having these giant reports. The people who are hired to write these reports will often tell you they think it’s a gigantic waste of time. I believe that NEPA should be dramatically scaled back and – this is particularly important – it should be run much much less by judicial review and adversarial legalism.

Now, if neoliberals don’t mind a little healthy constructive criticism, one thing that I think they’ve done is that they’ve overgeneralized a little too much from these cases and they get into this mood where they start jumping to conclusions any time they see any time they see any problem that even might even hypothetically be caused by overregulation.

There are other examples of proposals for deregulation that I disagree with. A paper written by James Schmitz, claims among other things, that excess regulation by HUD caused the market for modular housing to fail. This paper made the rounds, and was referenced by several prominent publications. I’ve looked into this and I believe it’s a basic factual error; the relative weakness of the market for modular housing just isn’t caused by HUD overregulation. Now I’m not going to go into this in detail, this just isn’t the focus of this essay, but I believe that HUD regulation on modular housing is getting it pretty much exactly right, and James Schmitz’ paper is simply mistaken about the facts.

Another example is that the infant formula shortage of 2022 was not caused by FDA overregulation. There was just a problem at one of the factories that makes a huge amount of our baby formula. Retail logistics and distribution operations don’t turn on a dime, it just doesn’t work that way. So when that happens there are going to be some shortages at our stores. Of course the FDA should be regulating the quality of our baby formula. America has one of the safest food supplies in the whole world; it’s a fantastic achievement of effective government. The FDA responded to the crisis exactly as they should: they waved some of the requirements given the emergency but not all of them. By the way, there are just tons of legitimate criticisms of the FDA! But specifically in terms of the infant formula shortage, no, that was not caused by FDA overregulation.

Niskanen critique of Libertarianism and Motivated Reasoning

One of the most welcome developments of the past few years has been a series of essays by The Niskanen Center, a new moderate think tank. I really loved these essays because they really got to the bottom of what’s really wrong with Libertarianism, and wrote about it all from top to bottom in a comprehensive and detailed way. There are several good essays they wrote, but one of my favorite ones is about how zealots engage in motivated reasoning to reach ideological conclusions. And I believe that what they describe is something that almost perfectly describes many nuclear enthusiasts criticizing the NRC. Nuclear Power is something that has an almost sort of cult-like following, and there are many people who are so emotionally invested in nuclear power, that they really are just not able to engage in an objective, dispassionate analysis of whether the failure of nuclear power is, in fact, caused by NRC overregulation.

Some regulations are good and some regulations are bad. In our country today, there are definitely examples of people jumping to the conclusion that regulation is good without really thinking very hard first. This nuclear question is one example of a situation where I see a whole bunch of people jumping to the conclusion that regulation is bad, in what I actually feel is a very unhealthy way, so I thought maybe I’d write an essay rebutting that position.

I think Supply Side Progressivism is great!

Supply Side Progressivism is an ideology that’s emerged recently, and it’s one that I agree with 80% of the time. Here’s Ezra Klein’s pitch of Supply Side Progressivism. In this essay, I’m going to disagree with Supply Side Progressives who are doing a whole bunch of other work that I broadly agree with.

One of the main things I agree with Matt Yglesias on is the political strategy that the forces of progress should use to try to get wins on climate. I believe that the political strategy the Sunrise Movement is following is just woefully misguided, to the point that the organization in its present form is arguably doing more harm than good. I don’t really like Lee Raymond very much, and I also think that he’s just factually not a significant obstacle to green energy. People obsessing over him are wasting their time, at best. The main political obstacle to progress on climate is that voters don’t want to pay higher prices for their energy.

I also agree it’s misguided to oppose new oil drilling. (For the next few decades) These restrictions would be worse than pointless, considering that in practice they only real thing they’ll accomplish is make Saudi Arabia and Russia pump more. Victory in the climate fight comes when we build the new green economy to displace the old one. That’s priority one, two and three. It really just doesn’t make sense to talk about shutting off fossil fuel production until we have something to replace it with.

The Institute For Progress is a new think tank that’s doing work that I broadly approve of on a wide variety of fronts. There’s no question that regulatory barriers to building new public works is really a significant problem facing America today (and the entire liberal democratic world in fact) and I commend many of their efforts along that front.

Suraj Patel was a candidate for Congress from New York, hailing to the Supply Side Progressive agenda. I think he’s great! His positions include a broad list of things I agree with. I had to cringe, just a little bit, when he wrote an article blaming the baby formula shortage on the FDA. Nothing about the seriousness of the problems our country is facing means that we should just jump to conclusions and engage in wishful thinking that all of our problems are caused by overregulation. In fact, the seriousness of our problems means that we have to actually do the hard work of figuring out what’s actually causing them; that’s what we have to do. I still think that Suraj Patel is awesome, and I hope he makes it to Congress someday, but pretending that all of our problems can be solved by a cookie-cutter program of deregulation, even when that just factually isn’t the case, doesn’t help anyone.

It’s obviously caused by NRC overregulation! It’s just obvious!

I’ve read a lot of different essays by a lot of different people criticizing the NRC. The main argument I come across, by far, is that nuclear power’s cost problems are obviously caused by NRC overregulation. I’ve talked to many people who seem genuinely and sincerely flabbergasted by the idea that anyone would even suggest that the NRC isn’t the problem. I think I’m reasonably good at reading if people are being honest with me, and I just think it’s fascinating that in their mind, the question is beyond debate. The main argument, and I’m being stone-cold serious about this, is that the troubles of nuclear power are obviously caused by NRC overregulation.

Y’know, I’m just saying, there’s another hypothesis for why nuclear power is so expensive: The fundamentals of the technology just are that expensive. Solar Thermal Power Plants, that use sunlight to heat and drive a turbine, failed because of cost. Offshore Wind Power is increasingly looking like it’s going to be a flop. Neither of those is (significantly) caused by overregulation; they’re caused by the fact that when you do all your work and make the technologies as best you can, they’re simply more expensive than the alternatives.

Just the brute fact that Nuclear Power is expensive is not, in and of itself, a particularly compelling reason to conclude that it's overregulated. Nuclear Power is expensive, yes. The question is whether the reason it’s expensive is because of safety regulations.

Yes, in 1974 Congress changed the name of the AEC to the NRC

The Atomic Energy Commission was the agency born out of the Manhattan Project to manage nuclear power. Over the years, there was a growing concern that there was a conflict of interest between the regulatory and energy development functions of the AEC. Also, they wanted to expand government energy research goals to all energy, not just nuclear energy. So Congress split the AEC into two new agencies. The Energy Research and Development Agency would do, well, energy research and development. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission would handle safety regulation and licensing of reactors. On Twitter, one of the first arguments you’ll inevitably come across goes something like this: Some people will claim that replacing the AEC with the NRC is what caused nuclear power’s troubles, and they’ll show you this graph:

This isn’t a serious argument. Here’s a good analogy: in 1947, Congress reorganized the War Department into the Defense Department. This graph shows the total number of casualties America had under the War Department and under the Defense Department. If someone told you that the reason we have so much less war now is that we reorganized the War Department into the Defense Department, would you find that argument convincing? The amount of war we have isn’t controlled by the name of the organization overseeing our armed forces. It’s controlled by the international conditions in the world, and the attitude of the prevailing political powers that be in America. And analogously, whether we build nuclear power simply isn’t controlled by borderline-cosmetic changes to the commission that licenses reactors. It’s controlled by the economic conditions in the country, and the willingness of the American body politic to use nuclear power. The decline of nuclear power in the 1970s was overwhelmingly a result of changing macroeconomic conditions that made nuclear power much less attractive, which we’ll explore.

The agency that was called the NRC in 1975 is, for all intents and purposes, the same agency that was called the AEC in 1974. William Anders was a commissioner of the AEC from 1973 to 1975, and then chairman of the NRC from 1975 to 1976. The remaining commissioners of the NRC were fundamentally drawn from the same class of people as the AEC; they were mostly apolitical career bureaucrats and some politicians. The same civil service that staffed the AEC was transferred to the NRC (and to ERDA). The foundational studies about nuclear power risk, done by the AEC, are used by the NRC as the basis for their analysis. The NRC started out by using the same regulations the AEC left them. Like, literally. Word for word. Of course they did then make amendments over the years. Many of those changes involved relaxing regulations, we’ll get to that next. The NRC operated under the same American political system, the same political pressures on whether to build reactors. For proponents of this theory, I guess my question is, what substantively changed about the regulatory approach between the AEC into the NRC? Can you be specific?

Keeping Reactors Safe: Probabilistic Risk Assessment

The lion’s share of NRC regulation is concerned with preventing a severe accident. A nuclear reactor is a complex machine with many overlapping and redundant safety systems to protect against the possibility of a meltdown. The Emergency Core Cooling System will make sure the reactor is filled with coolant, ideally even if much of the other equipment in the plant is failing. The Automatic Depressurization System will open automatically in the event that the pressure in the reactor vessel is too high, and vent some gas outside. The Reactor Protection System is a piece of control software that will continuously monitor measurements and then automatically order the shutdown of the reactor if necessary. Equipment has to be periodically inspected and tested. During construction, there needs to be documentation about how safety-critical components were inspected for quality control purposes. And so on. And finally, if all else fails, in the event of a meltdown, the Containment Building should at least keep the ruined reactor contained, and prevent too much of it from entering the environment. This is arguably the main reason the NRC exists, to ensure that adequate safety is taken to prevent catastrophic accidents.

To make sure that nuclear reactors are adequately protected against the possibility of a severe accident, reactor designs are subject to something called Probabilistic Risk Assessment. This is a general engineering discipline which is used to evaluate the safety of all kinds of things like airplanes. Here is an NRC primer on Probabilistic Risk Assessment. Here’s another. Probabilistic Risk Assessment involves looking at both the probability of a risk, and its severity. And it involves looking at the interaction of different risks. “What if a pressure release valve is stuck open and a pressure sensor is failing?”

Probabilistic Risk Assessment is the heart and soul of the NRC’s, and in fact the entire World’s, approach to regulating nuclear power plant safety. It controls all of the key decisions that really matter, and crucially, all of the decisions about what sort of expensive safety features are necessary.

Broadly speaking, here’s how it works. Some potential failure is placed inside a Fault Tree. Conclusions are drawn, like, “If this failure and this other failure happen, then something bad occurs.” A monetary value is placed on the ultimate amount of damage that that failure would cause. This allows you to perform a scientific judgment on whether some proposed change to the regulations is cost-beneficial. That’s a birds-eye view of the intellectual rubric that governs nuclear safety regulation. You can read all about this in detail in the NRC’s Regulatory Analysis Guidelines.

At the very very beginning of nuclear regulation, when this stuff was first set up, they didn’t use risk assessments to justify the rules. They started out with a prescriptive rules-based system where they would consult with experts, look at experimental test results, apply a little common sense, and then just say, “there’s a consensus that you have to do this to be safe.” I think it’s understandable that regulation started out that way, you have to start somewhere, but it’s equally important that they then had to put that system behind them and move to a more scientifically rigorous way of doing it. The business of shifting to a risk informed system began under the AEC, but was then mostly done under the NRC.

By the way, I would like to see this point addressed by the people who think that the decline of nuclear power is caused by the fact that Congress changed the name of the AEC to the NRC. Did the NRC change their standards when they took over from the AEC? The answer is yes, they did. They finished the business of risk-informing all of their rules. Everyone – regulators, experts, nuclear companies, and everyone else – agrees that these are better. This allowed them to conclude they could responsibly relax some of them. I would like to see this in particular addressed by the people who think the problem is that Congress changed the name of the agency that regulates nuclear power. (Of course, the NRC also did slightly tighten requirements in some other situations, yes.)

There's a variety of reasons why you can never shift to a completely risk-based regulatory system. There’s some situations where it’s just very hard to put a number on what the risk of a particular activity is. In those situations, you have to revert back to just a sort of practical, “well there’s a broad expert consensus and experimental results that show you have to do this to be safe.” The modern nuclear regulatory regime is referred to as risk-informed, in the sense that it uses a Probabilistic Risk Assessment and Cost-Benefit Analysis to justify regulations whenever it’s at all possible. The old prescriptive rule system never completely goes away.

To use a simple analogy, the USDOT has rules about how much sleep highway truckers are required to have. How do you quantify exactly what the risk of such a thing is? The problem is that we don’t have any experiments that directly measure what we’re looking for. But there are still things you could do. You could look at studies for how people’s decision making deteriorates after they’ve been sleep deprived for X hours. You could look at real-world crash data for drowsy drivers and try to see if you could glean out a relationship from that. Making such a determination within a scientifically rigorous cost-benefit framework would be a little difficult, but not impossible. If you’re hoping that this can all somehow be done mechanically, I have to say that that’s not really a reasonable expectation. Ultimately, good regulation is done when you use scientific, numerical methods to inform decision making, where expert analysis still guides the ultimate decision.

Protection from low-level radiation

Now, another regulatory concern is to protect public health from low-level radiation associated with the normal, non-emergency operation of the power plant. Nuclear plant employees, and the public, will be subject to radiation hazards. Like almost all public policy missions, nuclear regulation has several related parts, and it worries about the business of protecting public health from radiation, just like it worries about preventing meltdowns. This low-level radiation mission is arguably somewhat less important than the mission to protect catastrophic accidents. But it still has to be taken seriously.

As nuclear enthusiasts will be happy to tell you, nuclear power plants pose very very little risk to the public from their normal non-emergency operations. And to be perfectly clear, they’re absolutely correct! That’s really the key to this half of the mission, which is that there really just isn’t that much spending which is necessary to protect the public from the low-level radiation associated with the normal non-emergency operations of a nuclear power plant, because that is simply a very small problem to begin with. Nevertheless, there actually are some ways that nuclear power plants can pollute the environment radiologically. Let’s focus on just one of them:

When an atom splits, you’re left with fission products: an alphabet soup of elements spanning the whole periodic table. Of all of those, Krypton and Xenon are noble gasses that are relatively common in fission products. Most of these radioactive atoms will stay inside the fuel pellets. However, some of them will leak outside. So now we have radioactive gasses in the coolant loop. From there, what happens is a little different depending on what reactor type you have. In a Pressurized Water Reactor, they will accumulate in the Volume Control Tank. In a Boiling Water Reactor, they will get pumped out, on the other end of the turbine, by the Main Condenser Vacuum Pumps. From there, you need to separate those gasses out and store them as waste so that they don’t enter the environment. The regular, non-emergency operation of nuclear plants really poses very little threat to public health, but this is one example of a way that they do. And luckily it can be dealt with super cheaply, simply by separating those radioactive gaseous waste products, and putting them into a holding tank, and then just waiting for it to decay naturally.

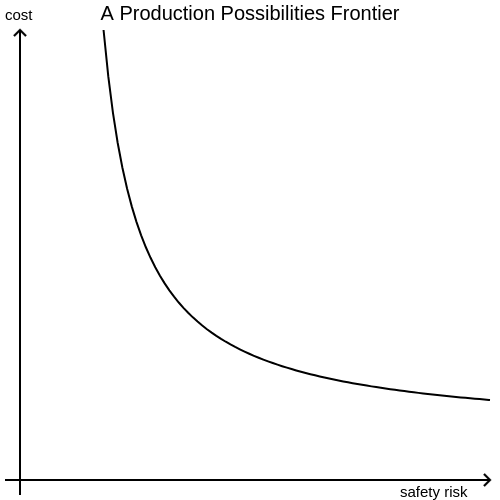

Production Possibilities Frontier!

If we’re going to design a nuclear power plant, we have all sorts of decisions to make about what sort of safety measures are necessary, and how they should be accomplished. What’s interesting is that there are actually sort of two different decisions mixed up together. There’s the question of how much we value safety; how much money we’re willing to spend to make a nuclear power plant safer. Then there’s also the question of, given a decision about how much we value safety, what is the actual best way to go about that, what are the correct engineering choices? How are we ever going to go about making these decisions in an intelligent way?

The answer is to organize our thoughts around a Production Possibilities Frontier, a concept which is ubiquitous in optimization and engineering and economics. You have multiple variables used to describe some sort of system. In our case, we have the cost of nuclear power and the safety risk of nuclear power. There are all kinds of proposals for how to build a nuclear power plant. Some of those proposals will go hard on safety and soft on cost, and some vice versa. If we graph the tradeoff between all these proposals, we get a production possibilities frontier.

Imagine walking along a frontier. At each point, the reactor becomes just a little bit safer and just a little bit more expensive. Or, if you’re walking in the other direction, a little bit cheaper and a little bit riskier. And crucially, there’s diminishing returns in either direction. When you’re way out on the safety side, and your reactor is very expensive, you could actually still make it safer if you really wanted to… but you’ve already used up all the low hanging fruit in that regard. At this point you’re talking about enormous expenses for very little benefit.

Now, to select a plant design, we will have to decide on how much we value safety. The idea of a monetary Value-Of-A-Statistical-Life might make anyone just a little bit like a sociopath, but I’m not aware of any way to do this optimization that doesn’t use it. It’s the only viable way. If you have some number that says how much you value safety, this will give us a utility function that is the sum of both variables, including some sort of conversion factor.

Every one of those diagonal lines on our PPF is an Indifference Curve; it has the property that we value all the points on that line equally. For every single point along any of those red lines, the utility function says they’re all “just as good.” If we were to walk along the line, we’d be exchanging $1 of cost for $1 of safety the whole way. Now what we want is the point that has the best combined value, the lowest cost of the plant and the lowest safety risk. To do that, we want to move as close to the origin as possible. That’s the green line. The green line crucially touches the Production Possibilities Frontier at exactly one point.

In general, technological advancement is associated with moving the frontier. In 1970, you could choose between various options of computers that were fast or cheap. In 1990, you had a new frontier, where there were options available to you that were just altogether better than the options you had in 1970. Technological advancement in nuclear power would hopefully allow us to move the frontier and get plants that are either cheaper, safer, or both, than what’s currently available to us.

Cost-Benefit optimization and ALARA

The business of deciding how much equipment is necessary to protect workers and the public from the normal, non-emergency operation of a nuclear power plant is done through a cost-benefit optimization process which was developed very early on when nuclear engineering emerged. It’s described as ALARA, “As Low As Reasonably Achievable.” ALARA involves listing all the available alternatives you have for controlling exposure to radiation, and their costs, and choosing the best global option.

Let’s return to a Production Possibilities Frontier, with an optimal point. If you’re walking along the frontier, it actually has the property that

before the optimal point, you’re exchanging less than $1 of cost for $1 in safety.

For an infinitesimal moment, when you’re right at the optimum, you’re exchanging exactly $1 in cost for $1 in safety.

After the optimum, you’re exchanging more than $1 in cost for $1 in safety.

And that mathematical property is the key to the process for demonstrating that you’ve done everything you can reasonably do to make the reactor safer. If you thoroughly document all of your alternatives, all of the things you could do would have costs that outweigh the benefits, you’re done. You’ve found the optimum. You’re as low as reasonably achievable. In the entire Production Possibilities Frontier, that point is the single best point with the combined value of safety and cost.

The Breakthrough Institute, and other writers with a generally libertarian bent, are pushing a critique of the NRC that centers ALARA as one of their main objections. However, their understanding of ALARA is badly mistaken. To start with, they’re sort of confused about the distinction between ALARA and the notion of cost-benefit analysis itself. Many of the things they attribute to “ALARA” are mathematical properties that are true of cost-benefit analysis generally. Cost-benefit optimization problems like this, with a Production Possibilities Frontier, is a mathematical concept which is as old as the hills. ALARA isn’t really a different mathematical optimization technique per se. Nuclear reactors are regulated by the NRC using cost-benefit analysis. ALARA is an engineering/bureaucratic process for demonstrating that you’ve performed cost-benefit analysis. It’s a way to draw up a formal document that says, “Here, I’ve reached the optimum. See, look, I’ve done everything I can do to make it safer. All the remaining possibilities to make it safer would have a marginal cost which exceeds their marginal benefit.” The Breakthrough Institute appears to be confused about this distinction.

Nuclear safety regulation is built on a solid foundation of cost / benefit analysis

Matt Yglesais writes:

Nuclear is not in that cost-benefit framework: It simply requires more health protection regardless of cost.

Ted Nordhaus of the Breakthrough Institute writes:

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s mandate, as several panelists emphasized, is safety above all else, including the economic viability of nuclear energy. This mandate differs from virtually all other environmental and public safety regulations, where incremental improvements to public health are balanced against the social and economic benefits that a technology or activity produces and the incremental cost of additional protections. Functionally, the NRC’s interpretation of that mandate has been to attempt to get risk associated with the production of electricity with nuclear energy as close to zero as possible, cost be damned.

And elsewhere, Ted Nordhaus writes:

As a result, the NRC has for decades endeavored to regulate nuclear risk and uncertainty as close to zero as possible, with no consideration of the cost to nuclear developers and operators of doing so or the environmental, public health, energy security, or economic consequences of not building and operating nuclear energy plants. No other environmental, public health, or safety regulator in the United States takes a similar approach, for the simple reason that limiting the purview of regulators in this way predictably results in regulation that reduces rather than improves public health and safety.

This claim is incorrect. Nuclear safety regulation is built on a rock solid foundation of cost-benefit analysis. The United States Code of Federal Regulations defines ALARA as:

ALARA (acronym for "as low as is reasonably achievable") means making every reasonable effort to maintain exposures to radiation as far below the dose limits in this part as is practical consistent with the purpose for which the licensed activity is undertaken, taking into account the state of technology, the economics of improvements in relation to state of technology, the economics of improvements in relation to benefits to the public health and safety, and other societal and socioeconomic considerations, and in relation to utilization of nuclear energy and licensed materials in the public interest.

When they talk about the “economics of improvements in relation to benefits to the public health and safety,” I think it’s really pretty darn clear what they mean. But just to be safe, let’s get it straight from the horse’s mouth. Here’s the Regulatory Guide, published by the NRC, on the subject of “Cost-Benefit Analysis For Radwaste Systems For Light-Water-Cooled Nuclear Power Reactors:” (That value of $1000 per man-rem has since been superseded by a different number)

Each applicant for a permit to construct or a license to operate a light-water-cooled nuclear power reactor and each holder of a license to operate a light-water-cooled nuclear power reactor should demonstrate by means of a cost-benefit analysis that further reductions to the cumulative dose to the population within an 80-kilometer (50-mile) radius of the reactor site cannot be effected at an annual cost of $1,000 per man-rem or $1,000 per man-thyroid-rem (or such lesser costs as demonstrated to be suitable for a particular case).

I don’t know how much more proof you want that ALARA is a conceptual framework fundamentally rooted in sound cost-benefit analysis. Here’s a document, authored by the Energy Department, that gives examples of how ALARA is applied in 10 practical radiation control problems. For each one, they put together a Production Possibilities Frontier, and then perform cost-benefit analysis using a social cost of radiation where they then pick the overall best option.

Libertarianism is an ideology that nominally accepts the need to correct for externalities, and then in practice, spends 110% of its time just fanatically, totally, absolutely opposing exactly that. Under the standard, boring model of economics that Libertarians claim to believe in, we’re supposed to require companies to spend money on pollution control when it’s welfare-enhancing.

Optimization using a Production Possibilities Frontier like this is the gold standard of cost-benefit optimization. In fact, it’s more than the gold standard, it’s mathematically impossible to do any better than that. The optimal point on the frontier is the point that scores best on the utility function; it has the best combined value of plant cost and safety risk. And that’s what ALARA is. It’s a process where you draw up a formal document and demonstrate and say “See look I’m at the optimum on the Possibilities Frontier. Of all the alternatives available to me, they have lower combined value than where I am now. Our choice is As Low As Reasonably Achievable.” For self-described “ordoliberal” types who claim to be motivated by a desire to have the economy achieve maximum theoretical efficiency, this is as good as you can get. They should be just jumping with joy about this if they’re actually motivated by the goals they claim to be.

No, ALARA doesn’t ratchet costs to infinity

Another claim you’ll hear from Libertarians about ALARA is that it causes safety costs to “ratchet towards infinity;” that it always demands increased spending, and never lets the price of nuclear power decrease. Here’s Jason Crawford, who declares himself “establishing a new philosophy of progress for the 21st century”:

This might seem like a sensible approach, until you realize that it eliminates, by definition, any chance for nuclear power to be cheaper than its competition. Nuclear can‘t even innovate its way out of this predicament: under ALARA, any technology, any operational improvement, anything that reduces costs, simply gives the regulator more room and more excuse to push for more stringent safety requirements, until the cost once again rises to make nuclear just a bit more expensive than everything else. Actually, it‘s worse than that: it essentially says that if nuclear becomes cheap, then the regulators have not done their job.

This claim is incorrect. In fact, cost-benefit analysis does in some situations require you to increase spending, but only when that increase is welfare-enhancing. And that simple fact is no reason to conclude that spending will ratchet to infinity.

An instructive analogy here is to look at something as simple as catalytic converters on gas powered cars. Once upon a time, there wasn’t any available technology to remove carbon monoxide and unburned hydrocarbons from car exhaust. Once that technology became available, at reasonable prices, the government certainly did require that it be installed. That is a regulation that very slightly increased prices, no doubt about it! But that requirement is welfare-enhancing; it’s what “Econ 101” demands. So it really is true that when a new safety technology becomes available, that sometimes results in requirements for increased spending. But this episode was not followed by the price of cars ratcheting to infinity. That didn’t happen, and there’s no reason to worry that would ever happen. In fact to carry the analogy a little further, electric vehicles are about to make cars both cheaper and more environmentally friendly.

If someone invents a new cost-effective environmental technology, a government that does environmental regulation under a rubric of cost-benefit analysis will require that technology to be adopted. That will slightly raise prices, yes. It will do that while concurrently increasing the public welfare more, in a way that’s welfare-enhancing. That’s the point. And none of this prevents other cost-saving innovations from also being adopted that lower prices. There are just tons of historical examples; air travel has seen fantastic price declines over the years while operating under an environmental and safety regulation regime that uses cost-benefit analysis.

Let’s look at technological advancement in the context of a Production Possibilities Frontier. The essence of technological innovation is that new possibilities arise which were not possible before; we have access to new points which were outside of the old frontier. Here’s a graph showing a status quo and then two new innovations:

In this figure, the Black dot is the status quo, and then we explore what might happen when two different technologies are invented, at the Red and Blue dots.

The Red dot is when a new technology is invented that offers environmental benefits at the expense of, yes, slightly increasing costs. So it’s like adding a catalytic converter. It’s welfare-enhancing to require spending on catalytic converters, notwithstanding the fact that it does indeed very slightly raise the price of a car.

The Blue dot is an example of a cost-saving technological innovation. It’s just as safe or, possibly, even slightly less safe, than the status quo. (In the graph, I showed it as slightly less safe, but it doesn’t have to be that way. There are plenty of innovations that are just as safe, or even more safe!) This is any sort of cost-saving product innovation. We don’t really have to pick a specific one; it’s anything that gets you the same result with less money.

The Green dot is when you apply the two innovations together. Both the environmental innovation and the cost-saving innovation are applied to yield a reactor which is both cheaper and safer than the status quo.

Jason Crawford says ALARA “eliminates, by definition, any chance for nuclear power to be cheaper than its competition.” I really cannot overstate how mathematically incorrect this is. It doesn’t eliminate that at all. The answer is that in order to decrease the price of nuclear power, you would have to invent a cheaper nuclear reactor technology which is either just as safe as the status quo, or even somewhat less safe. That’s it. The exact decrease in safety which it’s willing to tolerate would be determined by the utility function and the cost savings you’re offering. When you do that, the cost-benefit framework, which has been considered canon in nuclear engineering circles for decades, will respond by choosing that new design. Without even blinking. The cost-benefit optimization chooses the design with the best combined value of plant cost and safety. Simple as.

Does Jason Crawford somehow think that this optimization method makes it impossible to use the cost-saving innovation? No of course it doesn’t; in fact I’m kind of baffled that anyone would even suggest such a thing. Why would it do that? The graph shows all four possibilities: the start, with no innovations, with just one innovation each, and then with both. The winning point, the point that scores best on the utility function, is the one that has both the environmental protection innovation and the cost saving innovation applied. Adopting the cost-saving innovation does not “give the regulator more room and more excuse to push for more stringent safety requirements,” as Jason Crawford claims. The marginal utility used to judge the necessity of safety regulation is still the exact same as it was before.

If someone asked Jason Crawford if he supports the principle that the government should limit externalities within a cost-beneficial framework, I’d bet an ice cream sandwich that he’d roll his eyes and say, “Yes of course I support that. Stop it with this cartoon caricature of Libertarians.” (Or something along those lines) And yet, here he is, opposed to the platonic instantiation of just that. And not simply opposed, but opposed with this manichaeism, with this tone that seems to imply that ALARA poses nothing less than an existential threat to human progress. I encourage you to read his essay; it’s honestly quite enlightening to fully take in this tone that talks about ALARA like it’s a battle between good and evil with apocalyptic consequences for the future of humanity. I’m sorry but I have to repeat myself: Libertarianism is an ideology that nominally accepts the need to correct for externalities, and then in practice, spends 110% of its time just fanatically, totally, absolutely opposing exactly that. What he’s opposing is the most mathematically pure form of cost-benefit optimization that there is. The government requires that you spend on safety as long as the marginal cost is less than the marginal benefit to society, yes.

Nuclear Utilities are consistent with other utilities

The Breakthrough Institute says that the marginal cost used to regulate nuclear pollution is wildly out of synch with the marginal cost used to regulate other pollutants:

The NRC, through its Quantitative Health Objectives (QHO), As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) approach, proposed Alternative Evaluation of Risk Insights (AERI), and other radiological dose limits, sets radiological health thresholds and standards for both normal operations and rare design basis accidents. These standards are so low as to be entirely theoretical - meaning that health consequences associated with these exposures would not be statistically observable in a large exposed population, even over many decades - and are far stricter than those enforced for pollutants associated with similar energy production and industrial activities by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

This claim, that we have wildly different utilities for health threats from nuclear or other pollution sources, is incorrect. By the way, didn’t Ted Nordhaus previously claim that our nuclear regulation literally doesn’t use cost-benefit analysis at all? Now he’s claiming that it does, but just with standards for radiation that are “far stricter” than other pollutants? Even if that were true, he’s already conceding that the previous claim was incorrect?

Anyway, no, the marginal utility associated with public health damage caused by regulation is as close as we can get to the marginal utility used for other sources for environmental damage. This document explains exactly how the NRC arrives at its value of $5,200 per person-rem. They start with a Value-of-a-Statistical-Life of $9.0 million, which is an average of the figures that the EPA and the DOT use. They then multiply that by a probability that being exposed to radiation will give you cancer. There it is, straight from the horse’s butt.

When you compare these utilities, you run into a bit of an apples-and-oranges situation. If you want to compare the $9M Value-Of-Life to the $5.2K per rad-person, you run into the problem that you have to know how likely it is that someone will develop cancer when they’re exposed to a small amount of radiation. The problem is that this number isn’t known with exact precision. Insisting that the different utilities used for these calculations are exactly the same, to a T, is not really a reasonable demand. The problem is just that it involves too many numbers that aren’t known exactly. When an oil refinery emits an atom of mercury, what are the odds that it ends up in someone’s lunch, and what are the odds that it ends up at the bottom of the ocean, never to be heard from again? Well we don’t know that number with exact precision. The same thing is true about regulating everything from pesticides to paint. The only thing that you can demand is that these numbers be roughly similar. And the marginal utilities involved in regulating radioactivity from nuclear power plants versus other pollution sources, are roughly similar.

I don’t know exactly why the Breakthrough Institute believes that ALARA and dose limits lead to “far stricter” standards vis-a-v other pollution sources – their essays don’t really explain their reasoning – but I strongly suspect that they’re confusing a value with a marginal utility; they appear to be confusing the amount of pollution emitted with the threshold for cost-effectiveness for pollution control measures. Nuclear enthusiasts will be happy to tell you that coal-fired power plants expose the public to much more pollution than nuclear power. To be perfectly clear, this is absolutely correct! Coal, after all, is a mineral from the Earth, and so it contains all kinds of nasty things. There are efforts to clean those out of the exhaust, but those efforts are less than 100% effective, and so some of it leaks out anyway. The threat this poses to public health is much greater than the radiation risk from the normal, non-emergency operation of a nuclear power plant. But this simply doesn’t mean that the marginal cost used in the decision-making is different. That’s the fundamental error that they appear to be making. The amount of pollution emitted by coal plants is much more than the amount of pollution emitted by (non-emergency) nuclear power power plants. The marginal costs used to gate which pollution control measures are necessary is about the same.

How expensive is it, really, to just take the air that comes out of the Main Condenser Vacuum Pumps, and process it to separate radioactive contaminants? The answer is, it’s not expensive at all, it’s a tiny fraction of the cost of producing nuclear power, and it’s consistent with the $9M Value Of Life figure that we use in other contexts. So we should just do it. And we should do it, notwithstanding the fact that coal plants really do emit much more pollution than nuclear plants.

Nuclear Engineering is often insensitive to the social cost of radiation

It’s often the case that when people make arguments, the most important part is the buried premise: the part of the argument which is made implicitly. And in this case, people who obsess over the regulatory social cost of pollution are implicitly making the argument that safety spending is highly sensitive to the marginal cost you use for the social cost of radiation. In fact, most of the important questions about nuclear reactor safety design are relatively insensitive to the social cost of radiation.

What do we mean by sensitive? Well, let’s look at two PPFs. When you change the social cost of radiation, what happens? In one, it dramatically changes which point is selected as the optimum. In the other, it barely changes it at all. This is just a property of the underlying technology, and it happens to be the case that in nuclear engineering, these decisions are often relatively insensitive to the number you use as the social cost of radiation.

To be super clear about what we mean by insensitivity, let’s look at a contrived simple example. Say that we’re planning emissions control for an oil refinery, and we have three possible options:

We can do nothing to control emissions. In this case, the refinery will cause a statistical average of 10 deaths over its lifetime.

We can buy a relatively cheap emissions control. In this case, the refinery will cause a statistical average of 1 death. The equipment will cost $15M dollars.

We can buy an expensive emissions control. In this case, the refinery will cause a statistical average of 0 deaths. The equipment will cost $60M dollars.

To be clear, these aren’t actually real numbers; I just made this up. But the point is that in this example, the marginal utility associated with preventing the first 9 deaths is $1.7M, and the marginal utility associated with preventing the last 1 death is $45M. The EPA uses a Statistical-Value-Of-Life of $10.0M. What’s interesting about this example is that it’s just not even close; the first marginal utility is way below our threshold, and the second marginal utility is way above it. This is what it means for a Possibilities Frontier to be insensitive to the social cost of pollution. Even if you were to significantly change that social cost – by a factor of 4 in either direction! – it wouldn’t even matter anyway.

What this means is that for many of the safety decisions in nuclear engineering projects, even if you significantly change the social cost of radiation, and do the math, it just comes back with the same list of necessary safety features anyway. The Possibilities Frontier is insensitive to the social cost of radiation. This is the elephant in the room that all this obsessing over the exact marginal cost just totally misses.

As a thought experiment, let’s take this to the extreme. What would happen if you had a fully insensitive frontier? A fully insensitive frontier would be if you had a square corner. In that case, it mathematically doesn’t matter at all what you choose as your social cost of pollution. As long as it’s greater than zero and less than infinity, you choose the same plant design every time. Decisions about nuclear power plants obviously aren’t absolutely insensitive, but they are relatively insensitive. So when you change the social cost, it will change what safety equipment is required, but it won’t change it by very much.

In plain English, of all the proposals for safety features, many of them are obviously necessary, and many others are obviously unnecessary. If you significantly change the social cost, even if you stop using a scientifically rigorous cost-benefit altogether and just switch back to hard-nosed expert common sense, it does change the safety regulations, but it doesn't change it very much.

Ideological Zealotry Revisited

I’m sorry but I have to say that I find this argument from the Breakthrough Institute to be just totally unpersuasive. Imagine if someone claimed that the reason that Chrysler is doing so much worse than Tesla is that the government is forcing Chrysler to use a more expensive paint than Tesla. My response would be 1: No, the government is not forcing Chrysler to use a more expensive paint than Tesla and 2: Even if it was, I just cannot conceivably imagine that that would actually make a significant difference in practice anyway. And my response to the Breakthrough Institute is that ALARA, and our whole nuclear safety regime, is built on a solid foundation of cost/benefit analysis. The marginal cost for radiological pollution is as close as it can reasonably be to the marginal cost for other pollutions, notwithstanding some scholarly dissent on the matter. And in fact, the decisions about many of the key safety features are insensitive to the actual value, the actual number, you use as the social cost of radiation. Even if you significantly change that marginal utility number, it just comes back the same way anyway; it demands mostly the same list of safety features. All of this really just goes to show, in my view, just how misplaced the Breakthrough Institute’s obsessive focus on this is.

And in addition to all that, I’d also like to reiterate that the amount of money spent on controlling low-level radiation is a very very small fraction of the cost of producing nuclear power. The normal, non-emergency operation of nuclear reactors pose a real but small threat to employees and the public. Yes, the government has a regulatory framework that says that that threat has to be addressed within a rubric of cost-benefit analysis. The amount of money spent on that threat is small for precisely the reason that the threat is small to begin with, and it’s cheap to contain. This is all the more reason why ALARA is such an odd thing to focus on.

I’ve really spent a lot of time debating with Libertarians, and I’m used to them making claims like, “If we End The Fed, GDP will double in a month!” When they make these claims, they have a tone in their voice that’s somehow equal parts euphoric optimism and complete desperation. When nuclear enthusiasts make the claim, “All of nuclear’s problems are just caused by the fact that the NRC doesn’t use cost-benefit analysis,” this whole experience really feels very familiar to me. Like, it gives off the same vibes. Let’s revisit a passage from one of those Niskanen essays:

I’ve seen all of this before. When zealots of whatever stripe enter the realm of public policy, they almost invariably gravitate towards the weakest arguments, the dodgiest data, the most problematic theories, and the most dubious but convenient set of assumptions. That’s because the ends are so morally compelling (to them) that their interest in engaging in due diligence regarding arguments they desperately want to believe naturally flies out the window. If you don’t have a skeptical mind when you encounter arguments that you want to believe, you’re going to find yourself believing a whole lot of politically convenient nonsense.

Yes indeed. The key point here is that “The NRC doesn’t use cost-benefit analysis” is just such a seductive thing to believe if you’re emotionally invested in nuclear power, and distraught over the fact that it seems to be unable to match Solar or Gas on price.

When I come across the claim that “the US Government doesn't use cost-benefit analysis in regulating nuclear power,” my knee-jerk reaction is to say that this claim really requires further investigation. I would require extraordinary evidence to believe a claim like that. And – this is particularly important – I would require extraordinary evidence in the case where the people making that claim are these angry partisan zealots who are monomaniacally obsessed with pushing Nuclear over Solar. If your knee-jerk reaction to this claim is to immediately accept it at face value, my honest advice to you is that you should take a step back and sort of reassess your general strategy for judging the credulity of the things you read.

The NRC demands design changes during Licencing, not Construction

The Institute For Progress has also written essays placing the blame for Nuclear Power’s cost problems squarely on the NRC. Their essays make a number of criticisms, but one of the problems that they focus on the most is the problem of making changes to plans during construction. Their essay goes into considerable detail about how bad it is to make changes to the design of a large project when it’s under construction. And indeed it is! That contributes heavily to costs! Here’s the thing though: The NRC doesn’t demand any design changes during construction.

The NRC has a formal legal process for licensing the construction of nuclear reactors. When the NRC gives you a design certification, that’s the end of the process. The NRC doesn’t demand any fundamental design changes during construction at all; that’s just not how the legal process works. When you apply to the NRC for a license, they subject your application to intense scrutiny and send you all these detailed questions you have to answer and all kinds of other stuff. When you pass that process and get a license, that’s it. That’s the last chance the NRC has to object to the fundamental design of the power plant. You have a legally binding license which permits you to build a nuclear reactor with the design the NRC agreed to.

The Vogtle reactors in Georgia, the first nuclear plants in America in quite a while, faced unfortunate cost overruns and delays. The IFP writes that the NRC demanded a change to the Containment Building on the Vogtle reactors, “which had to be implemented on the in-progress Vogtle and VC Summer plants.” The NRC certainly did demand a change on those reactors! When they were in their licensing phase, in 2009. Construction started on those reactors in March 2013. That’s the point of the licensing process, to finalize the design of the reactors before construction.

Now, what is true is that the nuclear companies themselves have to make changes during construction for all kinds of reasons. There are very real cases of chaos during construction, but this isn’t caused by regulation, it’s caused by the companies themselves messing up. By the way, I’m not throwing shade on the nuclear companies by saying that; building nuclear reactors is hard and it doesn’t really surprise me that the companies occasionally mess up and have to redo work. I am 100% certain that if you put me in charge of building a nuclear power plant, I’d screw it up too, and have to take down some work and redo it. But it’s not caused by regulation though, that’s the point.

The IFP makes many other claims about the NRC, maybe someday I’ll have time to write about them all. But if you read their essay, I think you’ll agree that their principal criticism, the most stinging criticism they have of the NRC, is that it’s constantly demanding design changes during construction and this just utterly tanks productivity. This claim is simply incorrect; the NRC doesn’t demand any fundamental design changes during construction.

The NRC does occasionally demand backfits. A backfit is when you take a finished power plant design, and add some new piece of equipment. The NRC’s demands for backfits are really pretty small. And yes, all NRC backfits have to pass a cost-benefit analysis. But the main point is that a backfit, where you add some small piece of equipment to a finished power plant, is completely different than what the IFP is talking about, where you take a power plant under construction with 5000 construction workers on the payroll, and change the basic and fundamental design of the plant to the point that you have to take down a bunch of work, tear up all of your blueprints and start over. It’s totally different. The IFP writes:

A universal tenet of large construction projects is that one should avoid changing the design during construction. Changes while a project is in-progress may require existing work to be removed, or new work to be done in difficult conditions. It often requires significant coordination effort just to figure out what work has been already done (“Have you poured these foundations yet? Are the columns in yet?”). If a pipe needs to run through a beam, it’s easy to design the beam ahead of time to accommodate it. But if the beam has already been fabricated, you might have to field-cut a hole, or add reinforcing. Or maybe the beam can’t accommodate the hole at all, and you need to redesign the entire piping system (which will of course impact other in-progress work). While this expensive redesign is happening, everyone else might need to stop their work.

…

To summarize so far: In the U.S., labor costs increased dramatically, especially labor from expensive professionals. This labor cost increase was at least partly due to frequently changing regulations during the period, which caused extensive design changes, delays, rework, and general coordination issues on in-progress plants.

When you read this passage, it creates an impression that just grossly misrepresents the nature of any changes that the NRC demands after construction starts. The design of a nuclear power plant is selected during the licensing process. After a construction license, the NRC doesn’t demand any more changes to the basic and fundamental design of a plant. It’s true that the companies themselves sometimes have to make such changes, but that’s just isn’t caused by regulations. Any backfits demanded by the NRC after a construction license is issued are really very limited. The best way to answer this question is to go into specifics. Here is one of the biggest backfits the NRC has ever demanded:

After the Three Mile Island disaster, the NRC did a comprehensive analysis of when wrong. They determined that it was caused by operator error and instrumentation problems and things of that nature, rather than any fundamental problem with the design of the nuclear plants (like Chernobyl was). They responded with a plan that involved new training, as well as some instrumentation upgrades. This would apply to new reactors of course, but in this case, they decided it was so important that all reactors would have to be backfit as well. So that means finished reactors and reactors under construction. The NRC rarely demands further construction at reactors after they’ve already issued a permit, but this is one example of a time that they did. In fact it’s arguably the main example. In this case, one of the main changes involved control panel designs, which were carefully reviewed and modified in some cases to make things more clear to operators. They also had to install a new post-accident sampling system. Licencees also had to build a new Technical Support Center to provide space for more controllers during an emergency. You can look at page 188 of this document if you want a detailed description of all the changes. Information about exactly how much this cost will naturally vary by source, but the owners of the Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Station say the TMI backfit cost $35M.

That’s it. That’s one of the biggest backfits the NRC has ever demanded. (There were also some bigger backfits on some super super old reactors) Is the IFP correct to say that the NRC demands changes after construction begins? The answer is… not in the way that the IFP describes it, no. I really think that any reasonable person can tell the difference between the sorts of backfits the NRC demands, where you keep 99% of the design intact, versus the horror stories the IFP tells about what happens when you try to make changes to the basic and fundamental design of the power plant during construction.

The IFP is unambiguous in the sort of language they use to describe changes the NRC demands after construction starts. They worry about the “expensive redesign.” They talk about “extensive design changes, delays, rework, and general coordination issues.” They posit that maybe “you need to redesign the entire piping system.” There’s a very very simple answer to this claim: The NRC doesn’t demand changes like that during construction. That claim is incorrect.

I guess, my question for the IFP is, can they flesh this theory out? If they really think that regulatory backfits are one of the main causes of cost overruns, can they list the backfits that they think are responsible, explain how they disrupted construction, and how expensive that might have been? Because if they try to fill in the blanks on this theory, they’re going to find themselves trying to claim that redesigning control panels was responsible for a $1B cost overrun. Which is absurd. The documented cost of complying with the Three Mile Island backfit is literally orders of magnitude smaller than that.

I don’t know what’s causing construction cost overruns

I sure wish that I could give you a detailed account of what is causing construction cost overruns and how to fix it. Alas, I have to tell you the truth, which is that I don’t know what causes nuclear power plant construction to be so expensive. I will say that it looks to me, just from a birds-eye view, like the problems that are causing nuclear construction projects to be so unproductive are the same mysterious forces that are causing all our construction projects to be unproductive, but on steroids. The Anglosphere in general, and America in particular, has poor construction productivity. That really is a big problem that requires urgent attention! And one of the most troubling aspects of the problem is that we seem to have little idea what’s causing it.

The New York Times did a great story on how subway construction in NYC is no less than 10 times as expensive as it is in the rest of the world. The MTA and the builders blamed regulation as one of the reasons for the costs. The NYT looked into it and they say regulation is similarly strict everywhere. Even if you believe that regulation on inner city construction projects is excessive, that still doesn’t explain why construction is 10 times as expensive in NYC as it is in cities with similar regulations. Part of my problem with blaming things on regulation is that it serves as sort of a magic asterisk that says that there’s “one weird trick” that will make all your problems go away. There absolutely are problems in America that are caused by overregulation, but if you’re going to claim that, you have to have a factually scrupulous account of what the excessive regulations are and how you’ve concluded they’re causing the problem.

Nothing about the seriousness of the problem we’re facing means that we should just jump to conclusions about what’s causing it. In fact, it’s the opposite. The seriousness of the problem means that we have to find out what’s actually causing it for real. Saying that we have to really do the hard work, and find out what’s actually causing these cost overruns, that is the pro-progress position. Engaging in wishful thinking, saying that it must be caused by regulation, when there really just isn’t any factual basis to conclude that, that’s the anti-progress position.

The Nuclear Industry collapsed in the 1970s for macroeconomic reasons

The specific reasons that some large construction projects are so unproductive really is quite a mystery. However, what’s not a mystery is the general reason why nuclear power declined in the 1970s. The reason really has very little to do with safety, and is overwhelmingly because there was a macroeconomic environment which was simply not very favorable to building nuclear power in general.

The 1970s were a period of stagflation and slowing economic growth. One major factor in the decline of the nuclear industry is simply that demand for electricity itself slowed dramatically in the 1970s. The energy crisis of the 1970s had a profound impact on the American economy. Before 1974, electricity demand had been rising at 7% per year. The growth rate then settled to 3% per year. And even worse, utilities in the 60s and early 70s had been placing orders for new power plants expecting that growth to continue. When those growth predictions collapsed, they suddenly had this huge backlog of orders that they didn’t need anymore. So forget about building new plants, many utilities were canceling orders for plants under construction. During this time, interest rates also surged. This is particularly disastrous for nuclear projects that take out huge loans and only pay off after decades.

Utility privatization and marketization was another major factor in the decline of nuclear power. When a single public monopoly is in charge of the entire electricity industry from top to bottom, they can afford to embark on risky projects, knowing that if they go bad, ratepayers will be forced to pay for them regardless. The 1970s were a time where we switched from public monopolies to markets to supply power. Utilities considering nuclear power now risked bankruptcy and utter financial ruin if they ordered a nuclear plant. Peter Bradford, a former NRC commissioner, writes:

Nuclear-plant construction in this country came to a halt because a law passed in 1978 [PURPA] created competitive markets for power. These markets required investors rather than utility customers to assume the risk of cost overruns, plant cancellations, and poor operation. Today, private investors still shun the risks of building new reactors in all nations that employ power markets.

Don’t trust the word of a former NRC commissioner? Lol okay fine whatever. How about Professor Stephen Dansky, a widely published author on electricity markets who writes:

The purchase of a nuclear plant relies on bank financing and lenders emphasize the quality of the nuclear plant’s projected income stream to repay the financing. This is why all previous nuclear plant financings relied on the monopoly status of the purchaser with its legislatively anointed captive market to ensure an adequate income stream.

Today, due to deregulation, electric utilities can’t own regulated power plants in two-thirds of the country. In these states, electricity is generated and sold on a competitive basis by Independent Power Producers, end-use customers are free to choose their electric suppliers, and state regulators no longer ensure cost coverage of the nuclear-related risks.

When Ontario announced that they were buying four General Electric BWRX-300 reactors, several libertarian-leaning nuclear enthusiasts on Twitter remarked that isn’t it amazing what less government can do and why can’t we be more libertarian like Canada. The irony is that the reason Ontario is doing this is, in fact, because they have more government regulation of industry than us, not less. Ontario Power Generation is a public utility; it’s not only state-owned but has a legal near-monopoly on electricity generation in Ontario. Guys, it isn’t some sort of secret mystery why in America, nuclear power is something done primarily by the TVA and Southern state-owned utilities. And neither is it a secret mystery how France came to supply 70% of their electricity with nuclear power. It’s because they can make far-sighted, risky investments that the private sector really just doesn’t. The TVA is currently in exploratory talks to buy four BWRX-300 reactors as well. To my knowledge, the project GE is doing in Canada doesn’t have any fewer safety features than what it’s doing in America. Like, it’s the same model, the same reactor design. The NRC and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission work very closely together; they harmonize their activities as much as possible. What this episode shows to me is the just insane levels of confirmation bias and motivated reasoning that’s going on in these circles.

By the way, this is not meant to imply that utility marketization was a mistake. On the question of whether utility deregulation and privatization is a good idea overall, my personal opinion is that I think it’s a mixed bag, but I’m cautiously in favor of it. But no matter what you think of the wisdom of utility privatization and marketization on the whole, it’s a near-fatal blow to being able to finance nuclear power. By the way, the Institute For Progress wrote an awesome article on competitive markets for power! It’s one of the many things they’ve written that I highly recommend.

The basic idea of a Gas Turbine Engine is actually hundreds of years old, but until recently they barely worked at all. For a pioneering engine built by Franz Stolze in 1897, the compressor stage required more power than the turbine produced; the engine couldn’t run on its own power even with no load attached. Like so many of the technologies we use today, it was really seriously developed for the first time during World War Two, when Jet Engines were developed to propel aircraft. (By the time the engine was ready the war was mostly over) That technology was then readily adapted to generate electricity. General Electric sold their first land-based Gas Turbine Engine in 1949. The most recent machines are Combined Cycle Gas Turbines, which I won’t go into in detail but I think are really really cool. CCGTs achieve efficiencies of 62%, which is something that used to be just unheard of from any kind of fuel-burning engine. It certainly is an improvement over our friend Franz Stolze’s engine, which quite literally had negative efficiency. Also, advances in drilling technologies led to a huge boom of gas production in America and it became dirt cheap.

So let's add it all up. Starting in 1975, there really just wasn’t that much demand for new electricity generation to begin with. To the extent there was, much of that was met through new Independent Power Producers. Sky-high interest rates are just poison to nuclear finances. In the new marketized electricity generation regime, potential nuclear builders could no longer count on being able to dump cost overruns on ratepayers. And finally, in the 2000s when interest rates were low and demand started picking up again, gas blew the doors off of both coal and nuclear. All of this is just… not a very favorable economic environment for building new nuclear power plants.

The specific reason why these very large construction projects have terrible cost overruns is a tricky problem to solve with no obvious answer. The general economic conditions that lead to the decline of nuclear power is not really a tricky problem. It’s very well documented, and I would actually say it’s not really in serious dispute.

In this essay, Matt Yglesias categorically claims that "a huge wave of activism pushed, successfully, to make the regulatory burdens on nuclear power so large as to make it non-economical." This claim is at odds with the available data on the subject which says that the nuclear industry died for macroeconomic reasons.

My challenge to the safety skeptics

I have a challenge those who believe that safety is the main reason for high nuclear costs, and it goes like this: Can you show me a detailed nuclear power plant capital budget, which specific safety features you feel are unnecessary, and what the budget would look like if we removed those; how much money would we save?

And by the way, I’m actually not even necessarily talking about the NRC specifically here. There is, generally, a broad global agreement among experts about which sorts of safety features are necessary in nuclear power plants. Quibbles about the details, for sure, but agreement on the basics. If you really believe you’ve outsmarted them all, and you see opportunities for massive savings that everyone else has missed, I do think you should flesh your case out in detail. I don’t think experts are infallible, and if you believe they’re wrong, I’m willing to hear you out. Seriously! But the argument has to be more than hand-waving.

I think the best way to go at this is just with specific examples. Do you think that we require too much backup cooling systems? How much do you think we should require, and how much money would that save? Or do you think that we require too much documentation to verify that construction has proceeded according to quality standards? How much less documentation do you think there should be, and how much money do you think that would save? Are there people who think that reactors just shouldn’t have Containment Buildings at all? If there are really people who actually think that, I mean… okay, but they should say so explicitly and show us their cost/benefit analysis saying why they believe it to be unnecessary.

So that’s really my main question. My challenge to the NRC skeptics is simply to tell me what, exactly, the NRC is requiring that they shouldn’t be requiring. If it’s really true that the NRC doesn’t use cost/benefit analysis, then surely it would be easy to list all the safety requirements with poor cost/benefit, no? I don’t see why not. Here is the NRC’s final Design Certification for NuScale’s Small Modular Reactor. Ted Nordhaus says, “the NRC’s interpretation of that mandate has been to attempt to get risk associated with the production of electricity with nuclear energy as close to zero as possible, cost be damned.” If he really believes that, that means that the NRC refused to approve of the NuScale application until they added all sorts of silly expensive safety features that only a fool would think are necessary, right? Can he tell me what they are?

Anti-Nuclear zealots are hysterical and ridiculous

One last thing I’d like to add: It absolutely is true that anti-nuclear zealots are hysterical and ridiculous.

My High School History Teacher, who is a very very nice person that I remember very fondly, was more or less a leftist out of the 1970s; those were his political views. One of his big things was that he had this characteristic leftist fear of nuclear power. In fact, I’d say that was probably one of his top three issues that he cared about the most. It’s almost impossible to overstate just how over-the-top and hysterical this was. In his mind, he saw nuclear power as really like an almost sort of supernatural evil sent from Hell to cast a horrible thousand-year curse on us. It was honestly an interesting experience to see this anti-nuclear hysteria up close and personal. In their mind, they see it, truly, as nothing less than an apocalyptic battle between good and evil. Mr. M******, if you’re reading this, I think you’re a great person, and I respect teachers very much, and I had just so much fun taking your class! I learned a lot and had some great discussions. And I also think that your views on nuclear power are just utterly hysterical and ridiculous. I can’t lie, I’m sorry.

But with this point goes another complimentary point about nuclear enthusiasts. I think that quite a few nuclear enthusiasts way too easily make the jump from “anti-nuclear zealots are hysterical and ridiculous” to “nuclear power’s problems are caused by NRC overregulation.” That’s one of the main things I think is wrong with their thought process. In this essay by Matt Yglesias, I agree with his views about Paul Ehrlich and Amory Lovins. I agree that the degrowth movement of the 1970s was a bad thing. I suppose I also agree that in a “big-picture” sense, people generally significantly overstate the risk of nuclear power. But I’m really just as certain in my disagreement with his view that that’s what caused nuclear power’s decline, or even that nuclear power is overregulated at all.

Cranky activists think all sorts of dumb things that the political establishment just ignores. There’s a lefty movement around right now that wants to ban fracking, and/or ban any further oil drilling on federal lands. Congress ignores them. As well they should.

My Future Predictions

It’s fun to survey the landscape. Westinghouse is a historic American company that essentially pioneered the electricity generation industry. Just reading about them almost makes me feel like I’m stepping into a time machine and going back to the Gilded Age. Westinghouse built 60 out the 130 American nuclear reactors; GE is second with 42. They were doing okay until recently – not great but ok – when they opened a financial services division which made some disastrous bets which more or less ended the company. It got sliced and diced and sold off into a dozen pieces. If that’s not a depressing synecdoche for the financialization of the American economy, I don’t know what is. Well, anyway, now what’s left of Westinghouse is making a play for the nuclear revival. The Westinghouse AP1000 is a giant behemoth reactor that produces 1117 megawatts of electricity. Two reactors in South Carolina got canceled due to cost overruns. The other two at Vogtle were successfully completed, but their cost ballooned from $14 billion to $30 billion. This is the tragedy of the old-school nuclear power industry; they really just can’t seem to figure out a way of preventing this construction cost bloat. (By the way, the NRC didn't demand literally any backfits at all during the construction of these.)